Schedule a Call Back

Unequal wealth distribution: The natural outcome in an industrial society

Articles

Articles- Jul 11,25

Related Stories

India-EU FTA: How Will the ‘Mother of All Deals’ Affect Indian Industries?

The India-EU FTA offers India significant scope to expand goods and services exports through duty reductions and improved market access, though gains may initially favour the EU, writes R Jayaraman.

Read more

Indian manufacturing sector: Negotiating its way in a less VUCA world

India’s manufacturing sector is evolving through policy support, technology adoption and sectoral growth, though challenges in R&D and skilling remain, writes Prof R Jayaraman, Head, Capstone Proj..

Read more

The role of risk management in large projects

Risk is inseparable from project management, particularly in large and long-duration projects, where inadequate risk identification, ownership and follow-up often lead to cost and time overruns. Pra..

Read moreRelated Products

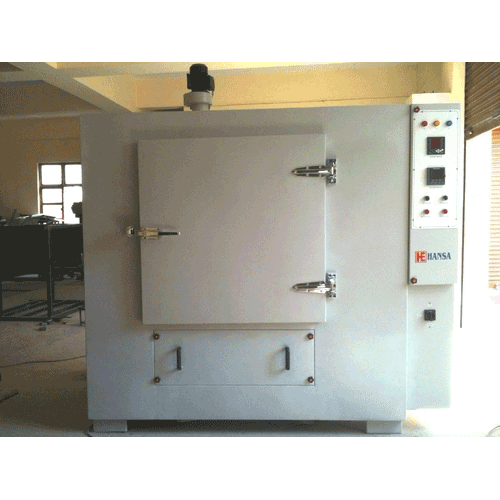

Heavy Industrial Ovens

Hansa Enterprises offers a wide range of heavy industrial ovens.

High Quality Industrial Ovens

Hansa Enterprises offers a wide range of high quality industrial ovens. Read more

Hydro Extractor

Guruson International offers a wide range of cone hydro extractor. Read more